How distracted driving evidence has fallen behind latest technological changes

TRL’s head of impairment research Dr Paul Jackson and head of behavioural science Dr Neale Kinnear argue that the evidence base for distracted driving has failed to keep up with technological developments and call for research to assess the distracting effects of the latest Human Machine Interfaces (HMIs).

The chief executive of Highways England has expressed concerns about the safety of in-car touchscreens and the potential for distracting drivers. This concern is echoed by many fleet managers, due to in-vehicle environments becoming filled with technology designed to assist (or entertain) drivers.

British law states it is illegal to hold a mobile phone or satellite navigation device while driving or riding a motorcycle. Drivers must have hands-free access, such as a Bluetooth headset, voice command, or built-in sat nav to use these devices legally.

The key research cited to support the law was conducted at TRL in 2002, which benchmarked the distracting effects of using hands-free and hand-held mobile phones against the effects of being under the influence of alcohol.

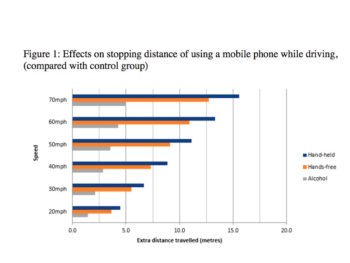

This study showed that using a hand-held device while driving increased response times by half a second; increasing stopping distance by over 15 metres when driving at 70mph. Even using hands-free increased response times and stopping distance by over 12.5 metres when travelling at 70mph (see Figure 1).

Since then, TRL’s simulated distraction test route has been used to investigate the level of impairment while driving caused by text messaging and using social networking applications.

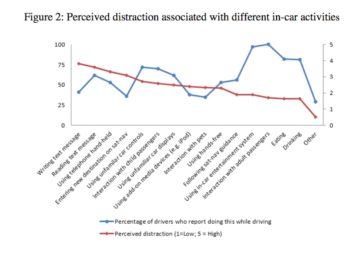

Research from 2015 suggested that the impact of distraction on safety is task dependent rather than device dependent. For example, text messaging is more distracting than a hands-free mobile phone call and using an entertainment system is more distracting than conducting a hands-free mobile phone call.

Further research has found that drivers see using unfamiliar car controls and car displays, or add-on media (e.g. music devices) to be more distracting than using a hands-free device (see Figure 2).

Although research can tell us about the distracting effects of mobile phones and earlier generations of Human Machine Interfaces (HMIs), there is concern that evidence does not reflect current technologies due to the rapid development of new in-vehicle technologies.

Over the past decade there has been an explosion of in-vehicle devices, creating a compound increase in distraction effects. Some devices are built into the vehicle by manufacturers while others are added through aftermarket products and technologies brought into vehicles by drivers such as smartphones.

Experts at TRL suggest that recent developments of HMIs pose a number of questions to the industry:

- To what extent is research based on mobile phone use relevant to modern HMIs?

- Is further research required to investigate the effects of interacting with the latest versions of HMIs?

- Should a limit be placed on the features added to HMIs, as was suggested by a panel of experts at a Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) Congress in 2016?

- Technology is advancing at a rapid pace. However, one feature of the driving environment that hasn’t developed is the driver. Using advanced simulators, TRL tests the latest in-vehicle systems and provides guidance to regulatory authorities and manufacturers to ensure that the technology and increased levels of driver assistance offered by new HMIs do not overload the driver.

This is particularly important when considering the move towards increased automation of the driving task. As information presented to the vehicle operator steadily increases, their role will gradually reduce to that of a system monitor.

Our research and understanding of this area suggest that the evidence base for measuring and monitoring driver distraction should be reviewed and updated to reflect the latest developments in HMIs. This should include an assessment of the effects of attending to multiple sources of information – not all of it relevant to the driving task.

For example, on behalf of IAM RoadSmart, TRL is using the DigiCar simulator to measure user performance when engaging with Android Auto and Apple CarPlay while driving.

Considering the influx of new technology in vehicles over the next 10 years, TRL is calling for up-to-date evidence to ensure that in-vehicle devices do not have unintended, negative consequences.